We see a lot of depictions of starships. Star Trek, Starwars, and countless others. I’d like to teach computers to make starships, and explore the design-space. But to do that, I’d have to know what a starship was in the first place!

So I turned to Jeff Zugale, who recently published Starshipwright One: Science Fiction Spaceships, a collection of 178 of his sketches and renderings, a few of which I have included sections of here as examples, but without permission. Hopefully he doesn’t mind. In perusing the pages, several patterns jumped out at me, which I have cataloged here for your perusal. I’d like to go over the major ones, and offer my own criteria for what it seems like would identify a starship, but apparently doesn’t, as well as what it seems to me is the single defining characteristic.

It’s not the engines

You’d think, for a ship that travels to the stars, you’d need a prominently featured engine! But no. While engines do feature prominently in a few designs, and an engineering section features in almost all (How do I know? Read on!) There are a significant number which have no evident means of propulsion and, indeed, a few that might not be able to move in any way. What makes these starships?

It’s not the living quarters

You’d think, for a starship, you’d need to have ship quarters. Some air-tight place for people to live. But no! While it seems that living spaces are common among most of the designs, there are a significant number that don’t seem to have inhabitants, and even a few that are explicitly unmanned.

It’s not the resemblance to aircraft or submarines

Perhaps starships are just like air-ships and marine-ships, but transposed into space? Nope. Quite a few of these designs bear no resemblance to streamlined vessels at all… though we are getting closer. I said no resemblance, but there is one thing they all have in common, and which they partially share with streamlined terrestrial vessels.

Which leads me to my definition…

What is a starship?

A starship is an artifact covered to some degree by an outer hull composed of multiple sections with visible seams between the sections.

This pattern holds true for every illustration in the book. And basically all of them outside the book as well. The flush-mount hull plates with visible seams is a consistent telltale for the “starship” quality. Certainly this is true of many other artifacts as well, submarines, airplanes, and most modern cars among them. The difference there is that, while terrestrial vehicles are fully covered by cowling, starships are only partially covered, exposing components beneath. Much like modern motorcycles, in fact. Starships are giant space motorcycles.

But why?

What does this particular aesthetic have to do with space travel? Why should it characterize all starships of popular fiction? Real spacecraft don’t have this kind of cowling. Why should all our fictional spacecraft carry this signature? My guess is the reasoning is two-fold, economy of illustration and appearance of affluence.

If we were to draw actual spacecraft designs, they would need to be scrupulously designed, with every ounce accounted for, and all components exposed which don’t need to be fully shielded. That stuff takes forever to draw! But you know what’s relatively easy to draw? Big old swaths of hull plating, with lots of seams to make it look neat, and a few inscrutable disconnected mechanical bits peeking out. Starships are covered with hull plating because it’s easier to draw than reality.

If we were to draw real spacecraft designs, they would need to be covered with un-interesting reflective insulation, thermal radiators, and bristly little bits of instrumentation. The are rife with spindly fragile looking deploy-able structures, bundles of free-floating wires, and weight optimized paper-thin structural brackets. None of it speaks of wealth. You know what looks real impressive though? Big old hull plates that are absolutely useless in space, except to look cool. Oh, sure, armor is helpful to shield from radiation and small debris, but I’ll bet it has more to do with invoking a plate-armored knight than realism. Plus airplanes, cars, and boats, the vehicles we are all familiar with, all have these kinds of hull plates, and the bigger the plates, the more expensive the vehicle.

So there you go, I think starships are drawn like giant space motorcycles because it looks expensive, and is actually cheap. Which just leaves us one final question to bring this exploration full circle.

Why Windows?

Nearly all starships have windows on them, and I think they play a critical role in the visual language that has developed over the years. I said earlier that crew cabins and engines seem like critical features for a starship, and windows are how these spaces are differentiated. Because the crew section has windows, and the engineering section doesn’t.

Usually, the “front” of the starship has the windows, and the “back” has the engines, with a fairly smooth gradient of window density from one end to another. More passenger-oriented designs will have more windows, and more utilitarian ones, less. As I said at the start, some starships don’t have quarters at all, but the ones that do nearly all follow this same pattern.

A Fascinating Topic

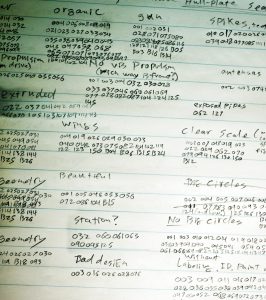

All this skips over the fascinating trends of antennas, weaponry, turbine-like intakes, and decals. You can examine my categorizations at your leisure, so I won’t bore you. Jeff’s book is available for purchase, and you can browse many of the sketches in the book on his Artstation page.

I’d like to make a computer game all about building these kinds of starships. Using the above rules, it seems possible to write procedural tools to make a starship out of any arbitrary shape. Then all that’s needed is some world-building context, some basic simulation systems, and away we go! Leave a comment if you’re interested in working on a project like that and I’ll throw a mockup together to play with.